The second meeting of the Healthy Housing for the Displaced Steering Committee took place on 6 February 2018 at the University of Bath and was attended by representatives of thirteen organisations including Allies and Morrison, Mott MacDonald, Protomax Plastics Ltd, Care International and Kingston University.

The International and Industrial Steering Committee meets bi-annually to monitor progress against work plan; provide advice on engagement with key users; provide advice on prototype design; ensure outputs meet key user requirements; provide advice on impact strategy and secure pathways to impact; and ensure project adds value and builds on existing knowledge.

The meeting started with the updates on work carried out in all packages. The team working on WP 1 recently returned from Nepal where they examined self-recovery in areas affected both by the earthquake and by floods. This was a scoping exercise looking at sourcing of materials and building techniques in the context of self-build. The team is going to carry out similar research in Turkey in March 2018.

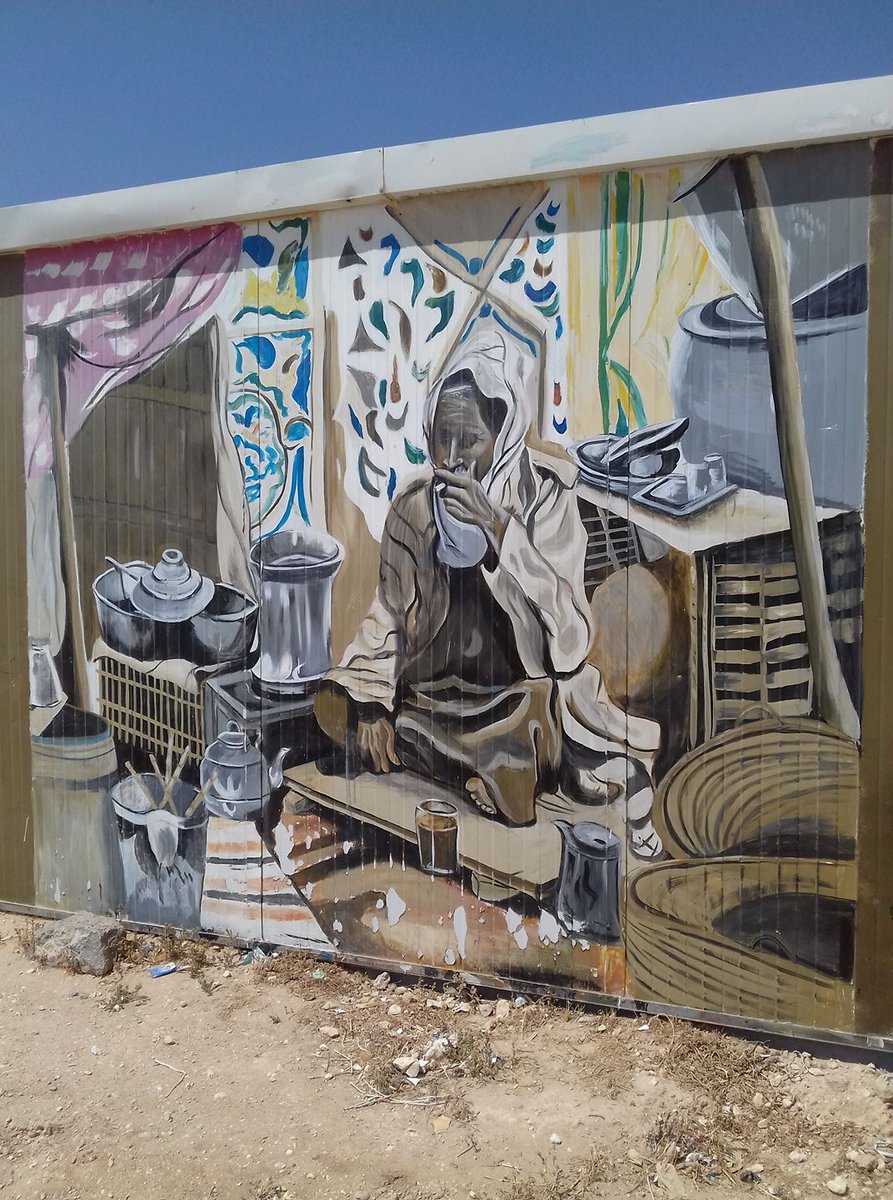

There have been two project publications published in Building & Environment, ‘Thermal Survey in Desert Refugee Camps’ and in Journal of Architecture, ‘Towards Healthy Housing for the Displaced’. The latter was awarded 2017 RIBA President’s Award for Research in the category of Housing. Another publication based on fieldwork carried out in Syrian refugee camps in Jordan is currently under internal review.

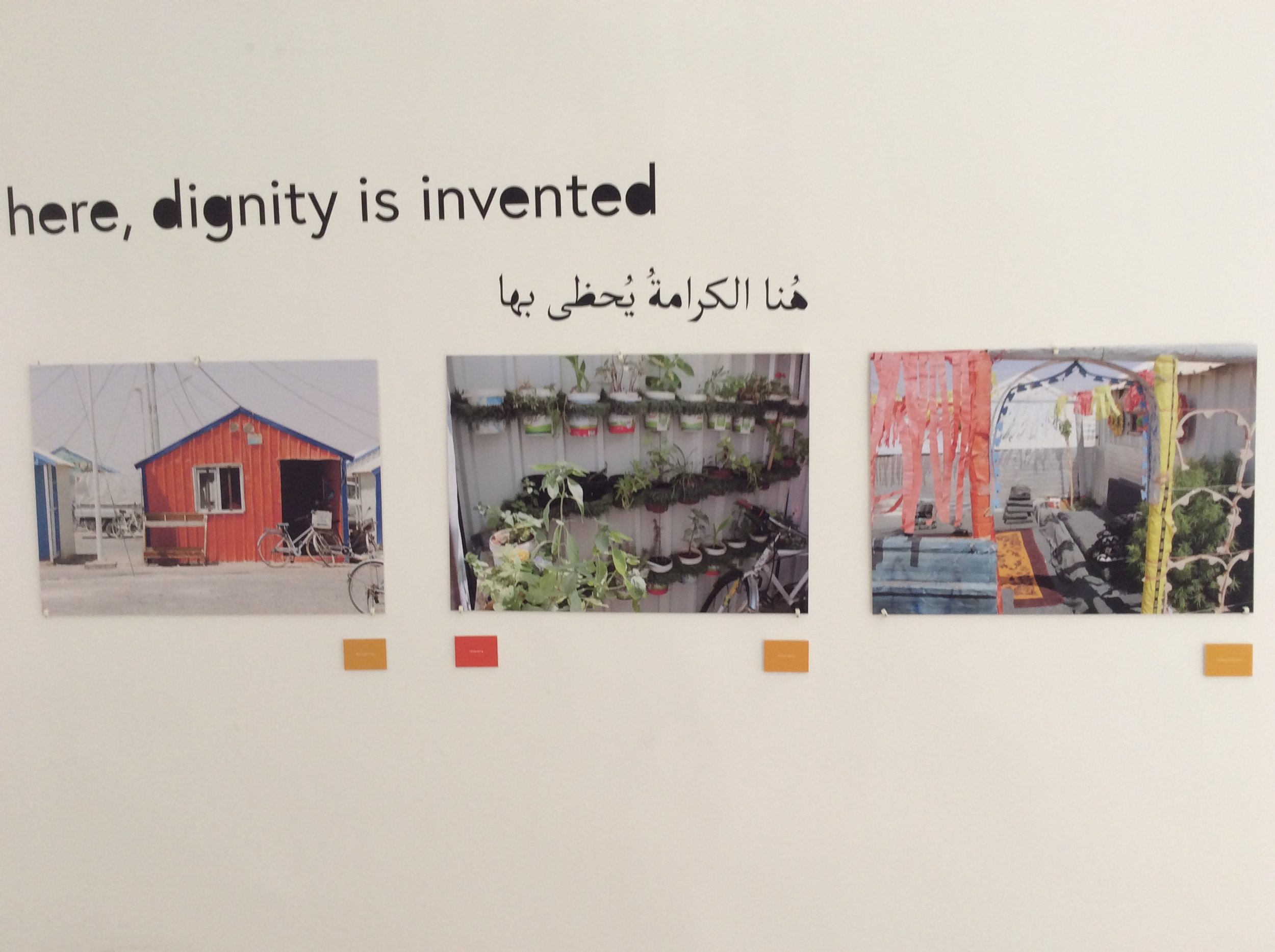

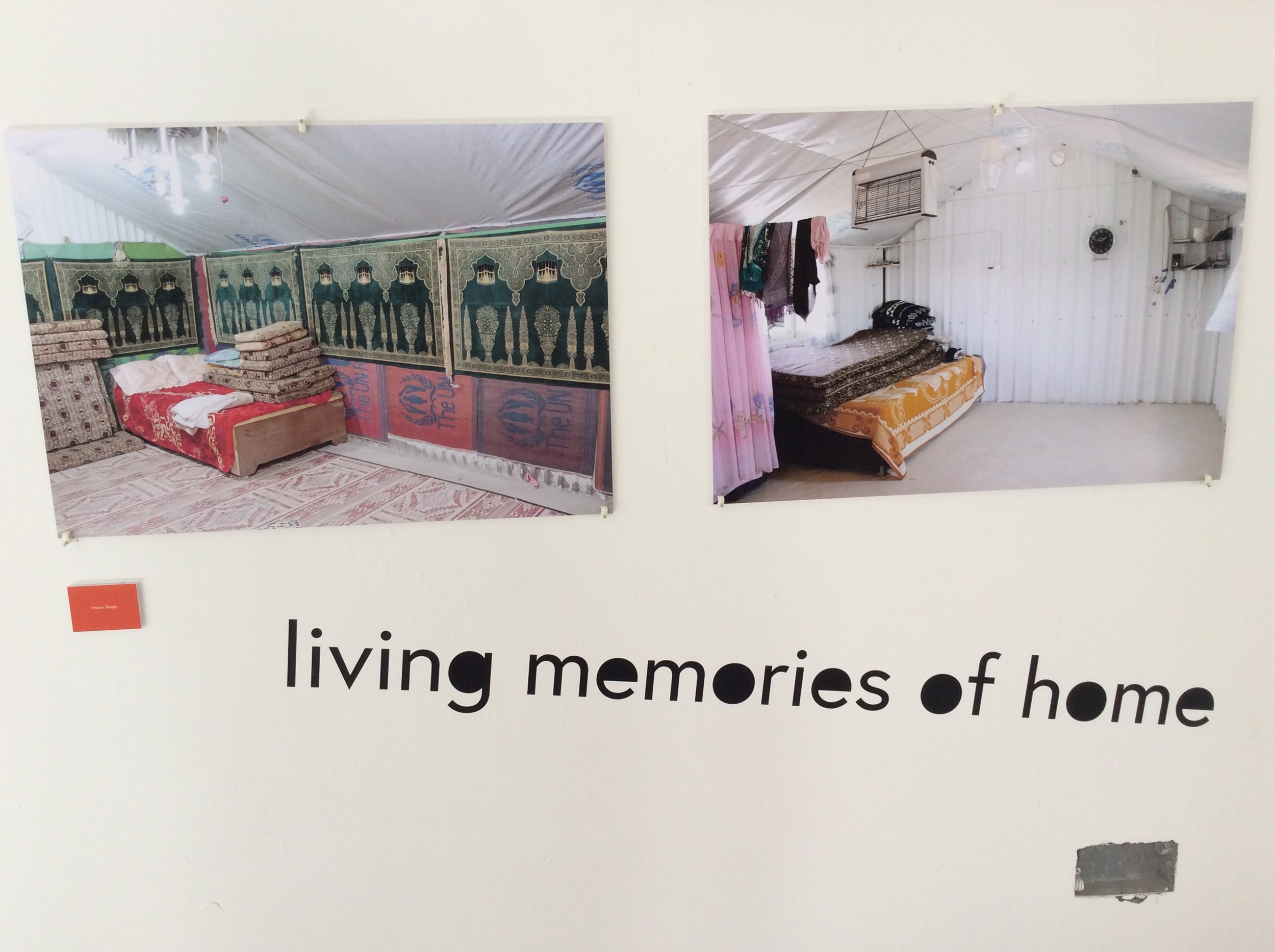

Work carried out in WP 2 is currently focused on re-evaluating Azraq refugee camp shelter design and investigating the potential for thermal performance improvement in this very hot desert settlement. This includes looking at increasing thermal mass that takes advantage of low night-time temperatures to dissipate heat gained during the day; introducing adaptable shading devices; increasing insulation; allowing cross-ventilation; using bonded insulation panels, which reduce condensation risk and increase durability of the construction and its thermal performance; and creating ventilated roof to purge warm air.

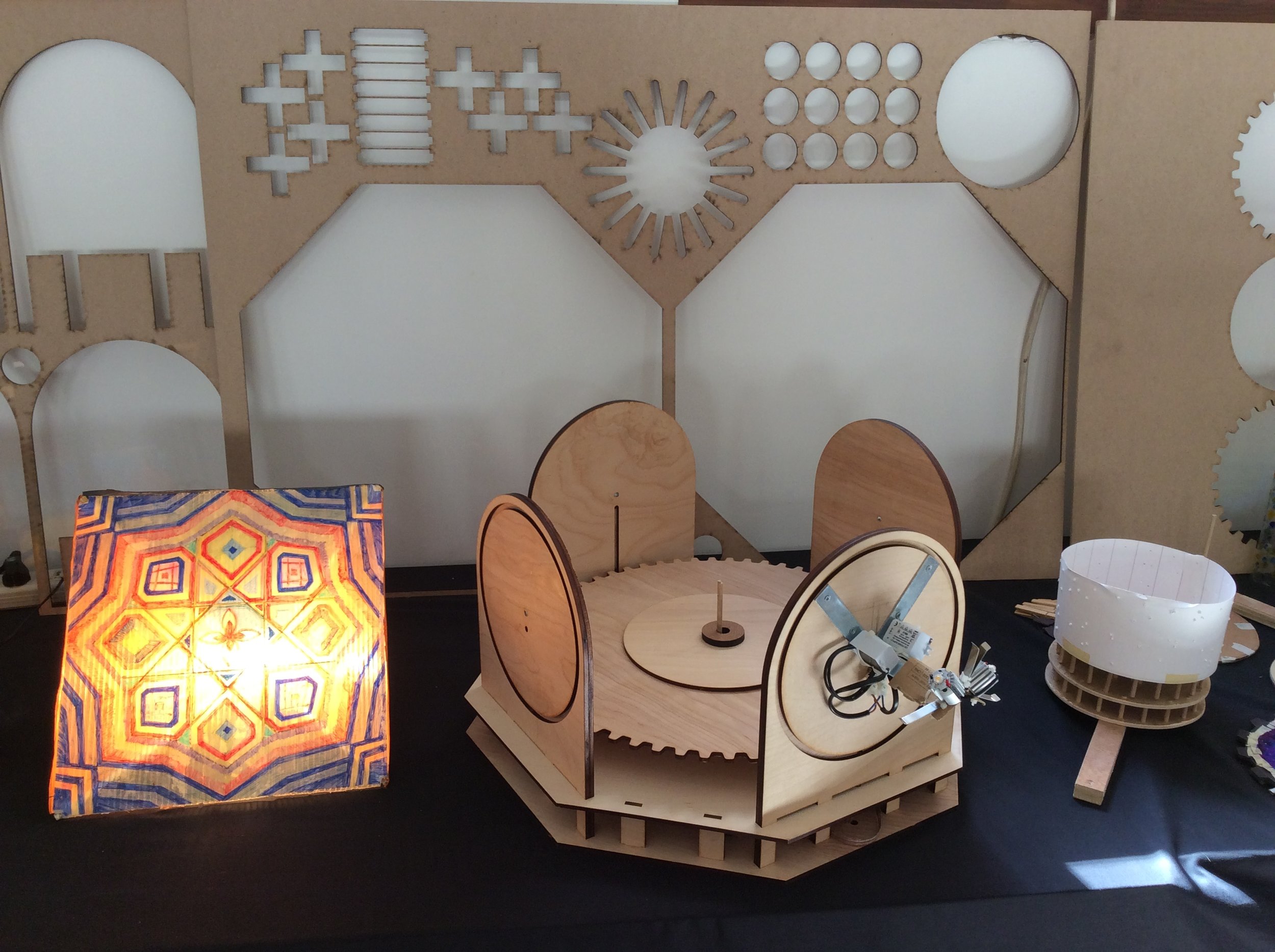

The objective of work package 3 is to lay alongside the necessary emergency/reactionary approach, a scientific one, where materials and form are co-debated, tested in a laboratory setting, then under test conditions, and later rolled out physically or as guidance. There has been Protomax Shelter constructed together with University of Bath students at the Building Research Park in Swindon. Second version of shelter is in design now. The researchers working on WP3 are currently analyzing SheltAir proposal, a pneumatic erection of gridshells, inflatable ‘office in a bucket’, and IKEA shelter in order to study thermal modelling.

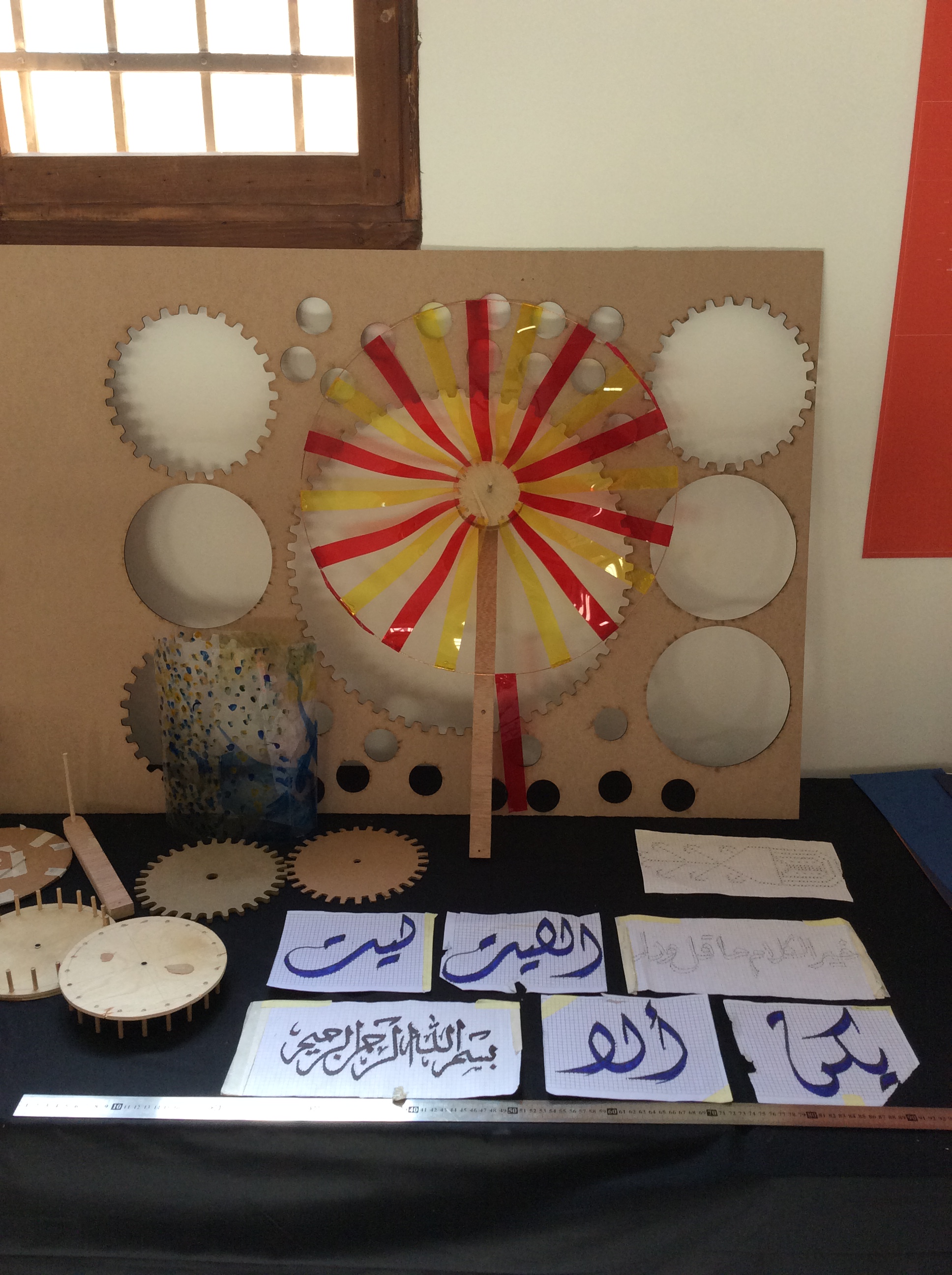

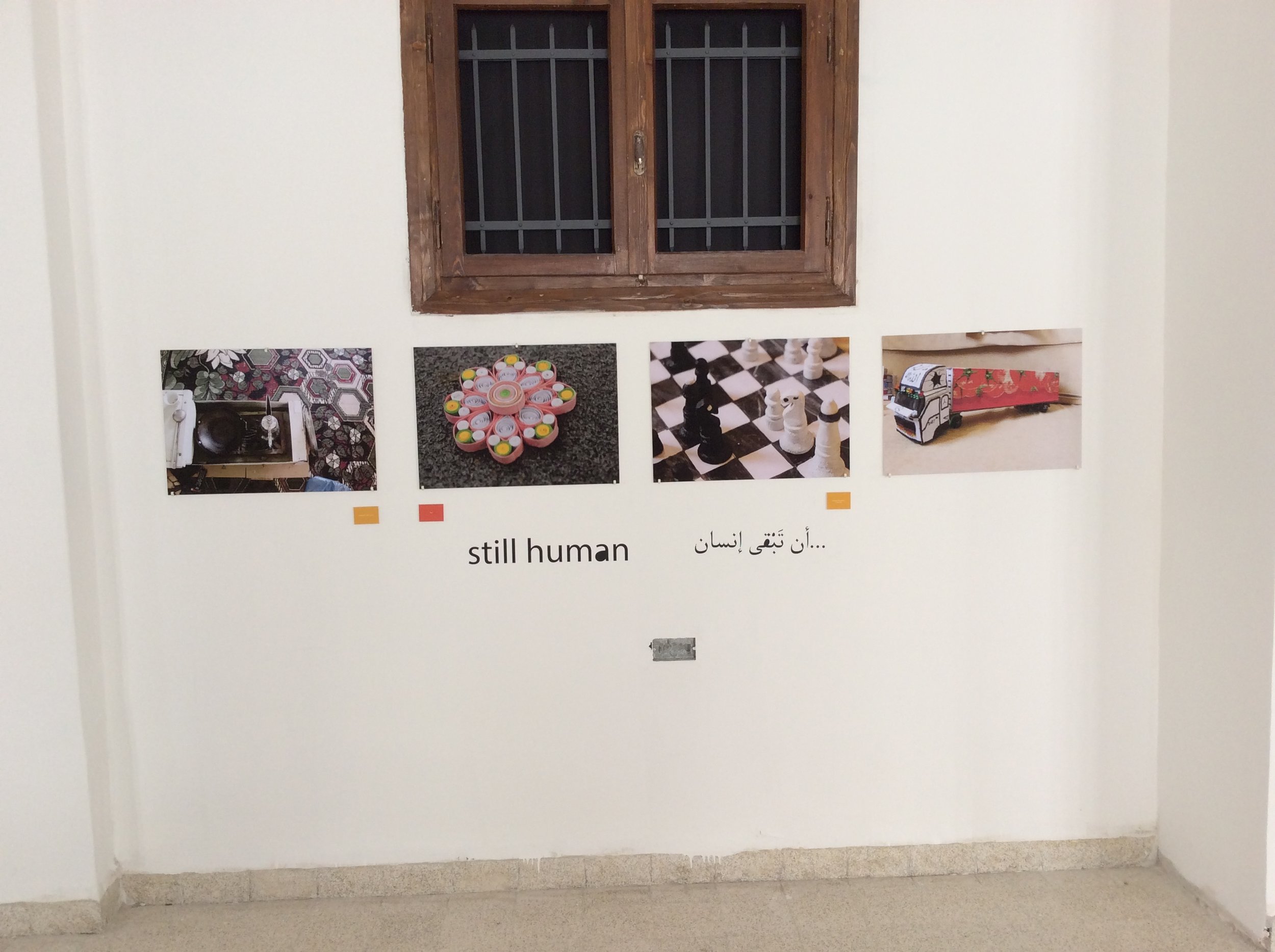

Work package 4 aims at initiating a science of shelter design and investigating new methods for the exchange of design information between researchers and camp residents which comprise of stakeholder-led design ideas and proposals; in-country user requirement definition; participatory design/refinement of proposed shelter designs; and an overall new approach to transitional shelter design.

The presentations updating the Committee on the progress of all work packages were followed by two parallel workshops on design typologies and design mapping focused on proposing new architectural, environmental and planning design solutions alongside scientific as well as technical approaches.

The participants came up with five design typologies, namely:

Typology 1: Clustered Courtyard

Small units (which can be of different sizes) represent spatial functions e.g. bedroom, living rooms, bathrooms that can be arranged and combined depending on the size of families. There is an inward looking internal courtyard for communal activities and privacy, and canopy to add environmental protection. This layout lends itself to controlled movement and circulation, whilst maintaining cultural practices without compromising on interactions within the family unit. An alternative format could be in the form of clustered extended family units.

Typology 2: Assemblages (modular form)

Module 3 dimensional forms use local materials in conjunction with modern materials such as panelised solutions. The form consists of indoor and semi-outdoor zones to deliver spatial hierarchy from external to internal spaces. The form can be built to reflect social and cultural preferences through the type and location of the building’s elements e.g. roofs, doors and windows. 3-d forms can be coupled or uncoupled; raised, sunk or situated directly on the ground.

Typology 3: Growth

Cell-like structures with a starting core similar to the previous concept. However, the emphasis is on growth with units allowed to expand linearly along pre-defined axes. The core is the fixed point but other components are designed to support expansion. Alternatively, units are linked together to create shared micro-spaces that could propagate linearly, in clusters or radially in accordance with vernacular typologies e.g. of row houses, or hierarchical dwellings.

Typology 4: Core and canopy

Combination of bulky materials (e.g. sandbag) and core enclosed by a lightweight structure. In essence, a combination of heavy and light materials. The core and light materials could be deployed as first response, whilst more stable materials can be added later. The form is however constrained within the boundaries of the external membrane but remains fluid internally.

Typology 5: Chimney

Wind tower central to the building form acts as a central focus for spatial functions, delivers thermal and ventilation comfort as well as provides structural stability. This type is perfect for hot climate, with its emphasis on natural stack ventilation/cooling from the chimney/wind towers. Depending on local climatic conditions it can ventilate from indoors to outdoors or vice versa.

The design mapping exercise highlighted the importance of flexible spaces (for instance, pods joined together, a frame/ kit of parts; coupling and uncoupling units; modular blocks, connected with dowels); low tech simple volumes with add-ons; and usage of local materials such as sand and earth for thermal mass. The design may be layered over time on the continuum from disaster relief to recovery, with a quick and simple first response to second layer that adds durability, followed by comfort and social areas. The structure should be lightweight, with low transmittance. We already know from our research findings so far that due to political constraints, shelters should not look permanent, but could nevertheless have surface texture. The definitions of comfort and socially acceptable shared spaces versus private ones are bound to differ in each cultural context.